Today, we are pleased to announce the incorporation of variant co-occurrence (inferred phasing) information in the gnomAD v2 browser. Phase refers to the genetic relationship between a pair of variants; that is, whether the variants are on the same copy of the gene (cis) or on different copies of the gene (trans). We are releasing inferred phasing data for all pairs of variants within a gene where both variants have a global allele frequency in gnomAD exomes <5% and are either coding, flanking intronic (from position -1 to -3 in acceptor sites, and +1 to +8 in donor sites) or in the 5’/3’ UTRs. This encompasses 20,921,100 pairs of variants across 19,685 genes. We envision that this data will be of tremendous help to the medical genetics community in identifying and interpreting co-occurring variants in the context of recessive conditions.

Background

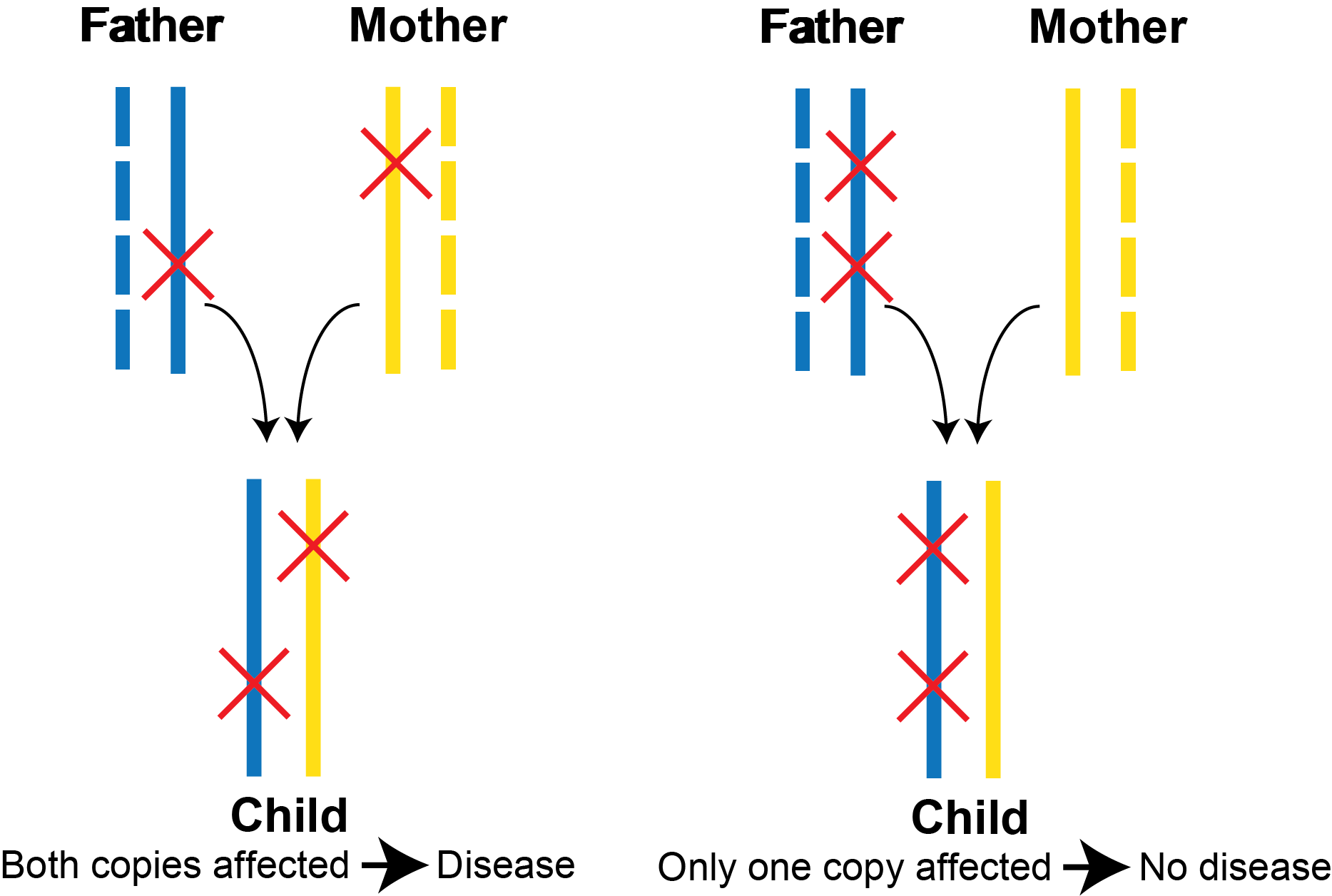

A pair of variants in a gene can occur in cis (same copy of the gene) or trans (different copies of the gene). This distinction has important consequences for interpreting the functional effect of a pair of variants. For an autosomal recessive disorder, both copies of a gene must have pathogenic variants in order to develop disease (i.e., occur in trans). This is illustrated in the example below. In these two example trios, the father’s transmitted copy of the gene is in solid blue, and the mother’s transmitted copy of the gene is in solid yellow. On the left, the child inherits one pathogenic variant from the father and one pathogenic variant from the mother. As both copies of the gene have pathogenic variants, the child is at risk for developing the recessive disorder. On the right, the child inherits both variants from the father, and because only one copy of the gene is carrying the variants, this is insufficient to develop a recessive disorder.

However, based on the child’s DNA sequencing alone, these two scenarios are indistinguishable in the vast majority of scenarios when short read next generation sequencing data is used. This is because most pairs of variants are further apart from each other than the length of a single sequencing read and thus their phase cannot be determined based on the child’s sequencing data itself. (See the “Multinucleotide Variants” section below for more details on how we handle coding variants that occur within 3 bp.) To overcome this challenge, clinical geneticists often sequence parental DNA. If the two variants are in cis, they should be both present in one parent. If they are in trans, each variant will be seen in a different parent. However, sequencing parental DNA increases cost, and parental DNA is not always available. Occasionally, we can apply long read sequencing to help infer phase, but this is still quite expensive to perform.

There are a number of accurate and efficient algorithms for determining phase for variants that are common in the population. However, phasing is not trivial for rare variants, which are the variants that are likely to be of greatest importance in Mendelian conditions. Additionally, exome sequencing data, in which the vast majority of the genome is not covered, does not provide enough density of surrounding variants to allow for accurate phasing. Phasing is also computationally intensive and can be technically challenging. Finally, phasing requires full variant data (i.e., more than what is available in a clinical genetic report), which is often not available to end users.

Approach

Here, we take a different approach to tackling these challenges. The genetic relationship between two variants (phase), is shared across individuals in a population. In other words, if two variants are in cis in many individuals in a population, then they are likely to be cis in a given individual’s DNA. Similarly, if two variants are in trans in other individuals in a population, then they are likely to be trans in a given individual’s DNA. These relationships are only disrupted by one of two processes:

- Recombination between variants. However, if variants are in close physical proximity to each other (as is true for most variants within a gene), then rates of recombination are low.

- Recurrent mutation. If variants arise independently multiple times in a population’s history, then the genetic relationships between them are not reliable.

Given that phase is shared among individuals in a population, we reasoned that if we could determine the phase between pairs of variants in gnomAD, this would allow users to predict these relationships for their samples.

After experimenting with a number of algorithms for phasing variants in gnomAD, we settled on a decades-old Expectation-Maximization (E-M) algorithm (Excoffier and Slatkin). We found that the phasing from the E-M algorithm was accurate, computationally tractable, and conducive to interpretation. The core idea behind this algorithm is that if a pair of variants are frequently or always seen together in the same individual in a population (i.e., co-occur), then they likely exist on the same haplotype. In contrast, if the two variants are rarely or never seen together in the same individual in a population, then they likely exist on different haplotypes.

We then determined the phase of every pair of variants within each gene in gnomAD, where both variants have a global MAF <5% and are either coding, flanking intronic (from position -1 to -3 in acceptor sites, and +1 to +8 in donor sites), or in the 5’/3’ UTR. We selected these cutoffs to reduce the computational and storage burden of this data, while focusing on variants that are likely to be of greatest importance in medical genetics. We performed these calculations separately for each continental ancestral population in gnomAD, as well as in aggregate across all gnomAD samples.

We validated this approach using 4,992 trios, leveraging the fact that we can uniquely phase variants using trios as a “truth” set. For this experiment, we removed individuals in gnomAD that were part of or related to the individuals in the trios. We found that we are 92-99% accurate for variants when they are on the same haplotype (cis) and 90-97% accurate for variants when they are on different haplotypes (trans), depending on the population. This remains the case even for extremely rare variants (<0.5% MAF), where we see similar accuracies. Phasing accuracy for pairs of variants that include singletons was generally lower (81-97%).

| Different haplotypes | Same haplotypes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | AF<5% | AF<0.5% | Singleton | AF<5% | AF<0.5% | Singleton |

| African/African American | 0.928 | 0.960 | 0.853 | 0.943 | 0.962 | 0.853 |

| Latino/Admixed American | 0.928 | 0.952 | 0.893 | 0.956 | 0.958 | 0.893 |

| Ashkenazi Jewish | 0.967 | 0.992 | 0.965 | 0.992 | 0.994 | 0.965 |

| East Asian | 0.896 | 0.947 | 0.897 | 0.942 | 0.949 | 0.897 |

| European (Finnish) | 0.963 | 0.984 | 0.960 | 0.988 | 0.990 | 0.960 |

| European (non-Finnish) | 0.896 | 0.908 | 0.811 | 0.924 | 0.922 | 0.811 |

| South Asian | 0.954 | 0.947 | 0.841 | 0.963 | 0.950 | 0.841 |

| All | 0.774 | 0.780 | 0.803 | 0.833 | 0.805 | 0.803 |

How to use the browser

On the variant co-occurrence page, users can input the information for any pair of variants within a single gene using a chr-pos-ref-alt format based on hg19/GRCh37 coordinates. The browser may return one of three possibilities:

- An error if one or both of your variants are missing in gnomAD. In this scenario, we are unfortunately unable to provide phasing information.

- An error if any of the following conditions hold: the variants are not in the same gene; at least one variant occurs at a frequency >5%; at least one variant does not occur in the supported regions (coding, flanking intronic, and 5’/3’ UTRs).

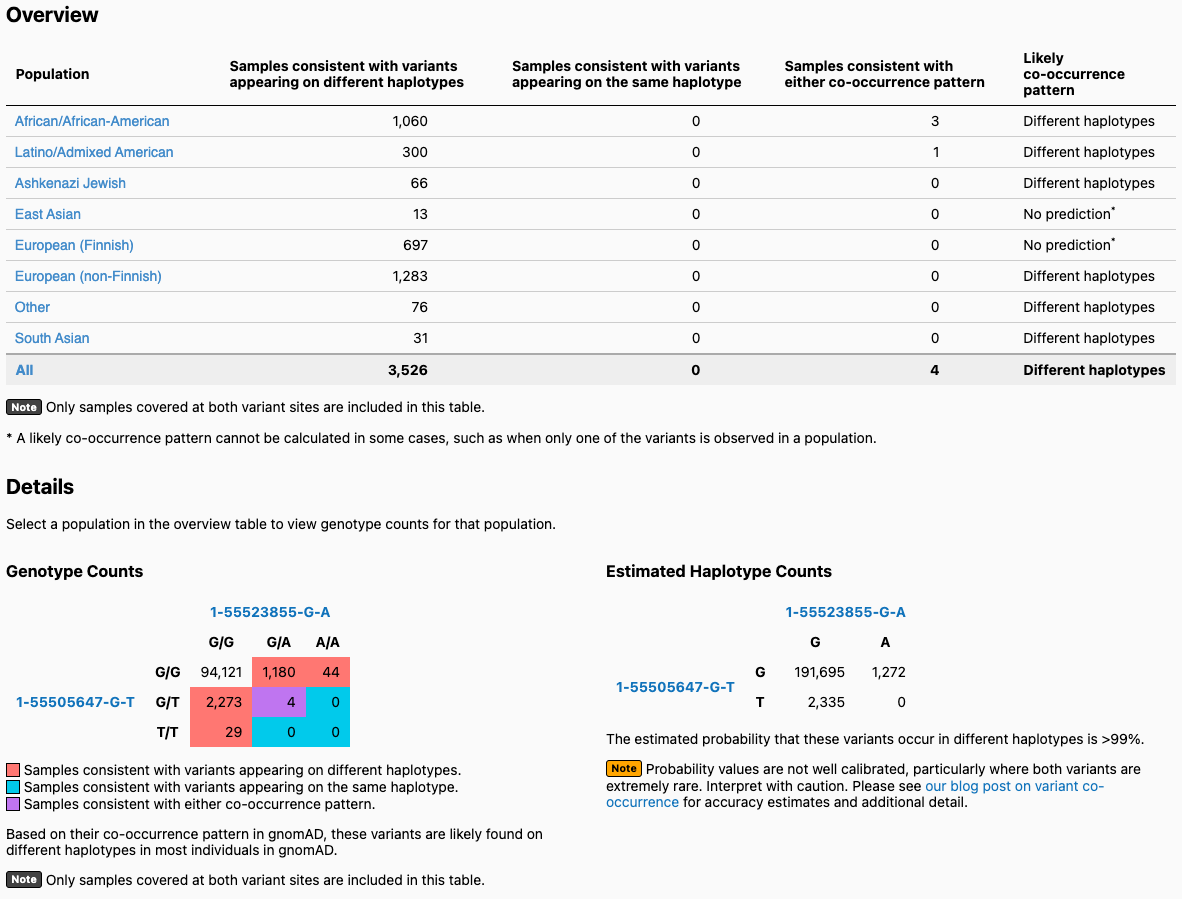

- A detailed output window, an example of which is shown below. Let’s use two variants (1-55505647-G-T and 1-55523855-G-A) in the gene PCSK9 as an example. When you enter these two variants on the landing page, you will get the output page displayed below. On the top, you will see a table broken down by continental ancestry. For each ancestry, we list how many exomes in gnomAD from that ancestry are consistent with the two variants occurring on different haplotypes (trans), and how many samples are consistent with their occurring on the same haplotype (cis). Below that, there is a 3x3 table that contains the 9 possible combinations of genotypes for the two variants of interest. The number of exomes in gnomAD that fall in each of these combinations are shown and are colored by whether they are consistent with variants falling on different haplotypes (red) or the same haplotype (blue), or whether they are indeterminate (purple). On the bottom right, you will see the estimated haplotype counts for the four possible haplotypes for your two variants. These are the haplotype counts estimated using the EM algorithm, and they allow us to predict whether your variants are more likely to be on the same or different haplotypes.

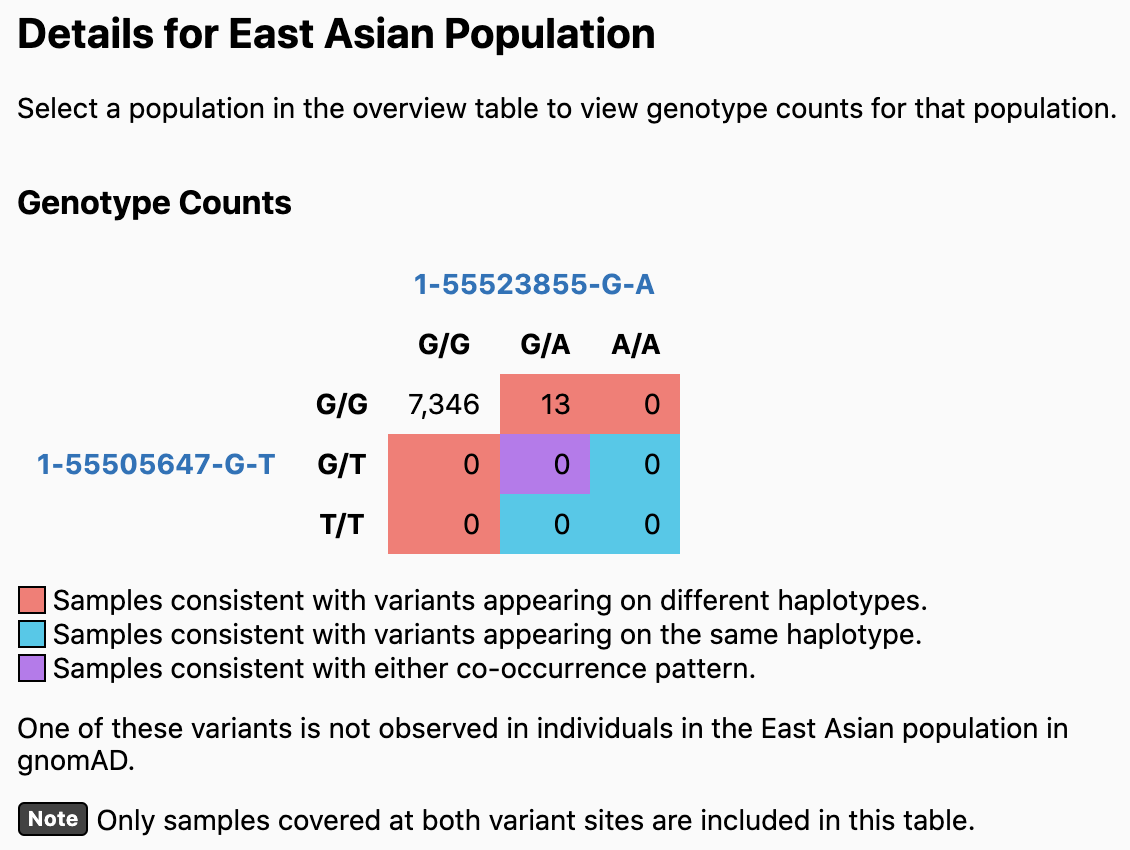

In this example, the two variants are predicted to be on different haplotypes in most populations. If you click on a population (e.g., East Asian), the values in the Genotype Counts table are updated to reflect counts in the specified population. In this case, one of the variants (1-55505647-G-T) does not appear in any East Asian individuals, so no prediction can be made.

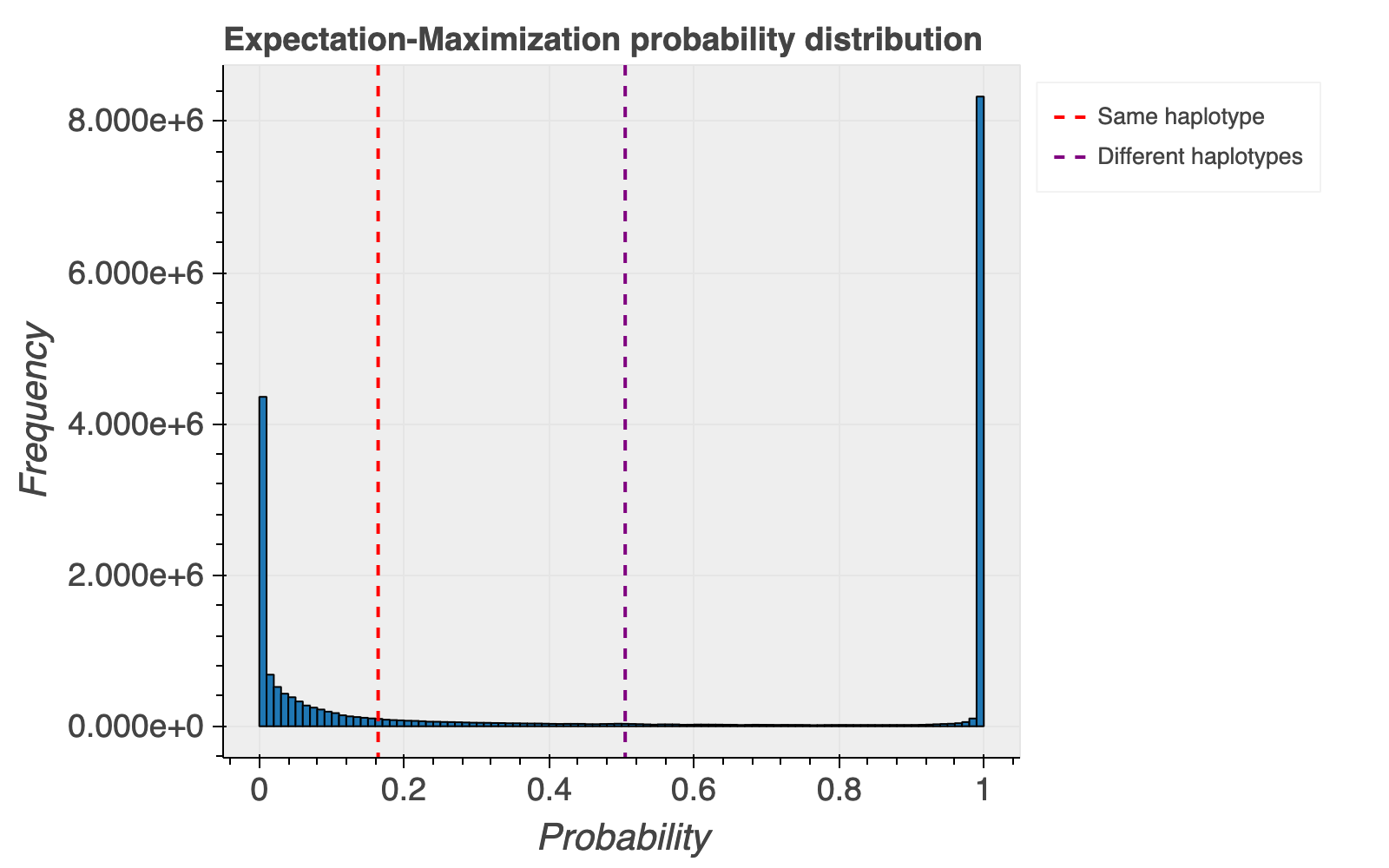

Based on the haplotype estimates, we also calculate probabilities that a pair of variants are on the same or different haplotypes. The overall distribution of the probability of each variant pair occurring on different haplotypes is shown below for reference, with most variant pairs falling at the extreme ends of the distribution.

We caution users not to overinterpret the provided probabilities for whether variants are more likely on the same or different haplotypes. These are not well calibrated and often based on small numbers of exomes, and we intentionally do not assign statistical significance to these numbers.

Multinucleotide Variants

This isn’t the first time that we have looked at patterns of co-occurrence in gnomAD data — we have previously published on multinucleotide variants (MNVs), which are cases where multiple variants are present close together on the same haplotype. For these variants we are able to use a more accurate approach to determine co-occurrence, taking advantage of the fact that variants that are present in the same read must be on the same haplotype (termed read-backed phasing). Our browser uses this approach to annotate and flag nearby (<3 bp) coding variant pairs in the same codon in cis, as these can have a distinct effect on the protein sequence relative to the individual variants. Because the read-backed phasing approach is more accurate than the statistical phasing approach discussed above, we recommend that users rely on MNV annotations if those are available. We have added a link to the MNV page for pairs of variants where this information is available.

Caveats and limitations

A key limitation to our current approach is that many Mendelian disease variants are exceedingly rare in the general population, and phasing accuracy for extremely rare variants is generally lower. Additionally, variants in a given individual are most accurately phased when based on data from the corresponding ancestral population. However, the sample sizes for some ancestral populations in gnomAD are still relatively small, limiting the accuracy of the phasing for these populations. As additional, ancestrally diverse samples are added in future gnomAD releases, we will be able to update our calculations to improve our accuracy; and we will also be able to phase a greater number of variant pairs.

The accuracy of phasing also depends on recombination and mutation rates, as alluded to above. If there is a recombination hotspot between a pair of variants, or they are far apart (as can happen in a very long gene), then recombination can disrupt the genetic relationships and render this approach less accurate. Also, if a variant is recurrently mutating (and thus arising recurrently on multiple haplotypes), our approach will be less accurate.

Conclusion

In summary, we leverage the size of gnomAD to provide a new resource to the medical genetics community on the phase of rare variants. We hope that the variant co-occurrence information now displayed in the gnomAD browser will greatly aid in the interpretation of co-occurring variants, and we encourage users to write to gnomad@broadinstitute.org with comments and suggestions for improving this feature.